Like many people, I have a large collection of online accounts to manage. Examples for me include various email accounts, Twitter, and this blog. My large collection means that I have many passwords to manage. I like to think that I create passwords that are reasonably secure as well as being memorable for me, but its an annoyance to do so on a large scale.

Despite their many drawbacks passwords are currently a pervasive part of online life. While it’s easy for some to mock users for using unsafe passwords, a more nuanced approach is to understand that people are quite adept at circumventing security that gets in the way of their goals. Donald Norman has written eloquently about the challenge of designing a usable product with security in mind.

Some of the usability challenges around managing passwords were reiterated for me when I recently updated the passwords associated with my various online accounts. By sweeping through all my accounts at once, I got a concentrated look at various design solutions used by service providers to support password management by their users. The results were decidedly mixed in terms of usability. This message on restrictions in creating a password wasn’t unusual:

When changing your password, please remember that it must be between 5 and 8 characters in length and should contain both letters and numbers. Special characters (e.g. #, &, @) must not be used as they will not be accepted by the system. Passwords consisting of all letters or all numbers are not recommended.

While the message is clear, the underlying restrictions make it hard to come up with a secure, yet memorable, password. (As an aside, I’ll add that while I have my own strategies for creating and using passwords, I’m not going to describe them here. I hope the reasons are obvious!)

There are approaches to password creation that improve things a little.

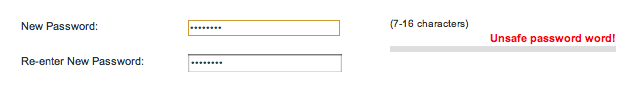

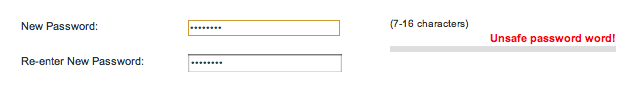

One popular UI widget provides immediate inline feedback on the strength of a password that a user has defined for an account. I found several examples during my recent updates. Here’s one in particular that shows the feedback when I type in a terribly weak password for the account.

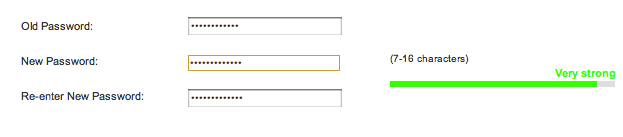

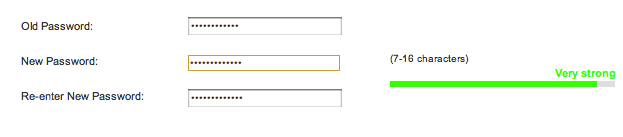

Not bad. The wording isn’t optimal but “Unsafe password” gets the job done. Here’s what appears when I provide a more secure password that includes a mix of letters, numbers, and special characters:

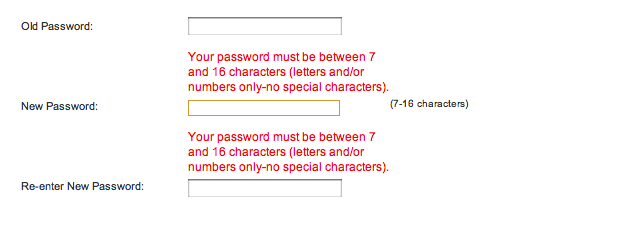

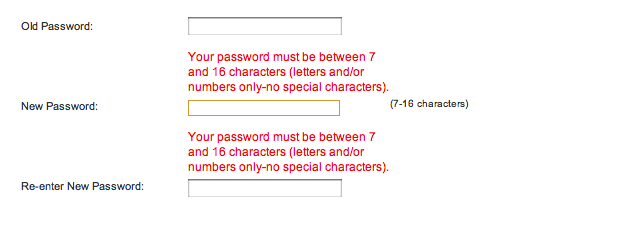

Again, the wording isn’t optimal but “Very strong” is fairly clear and also reassuring. Of course, the feedback is only useful when the guidance that it provides can be acted upon. Here’s what I see after trying to save the new password:

It turns out that my “very strong” password choice is too strong for this service!

Obviously, security is far from an easy problem to solve, and no single solution fits all needs. Having said that, this particular example from just one small sliver of a secure system is clearly bad design from a user experience perspective. The initial feedback is accurate in its assessment of the security of my desired password, but it’s irrelevant because the system won’t accept the password. The later feedback comes at a point in the workflow where it’s more frustrating than informative.

If passwords have to be a part of a product or service, design for them in a way that doesn’t needlessly decrease usability.