We had a fun day at Boltmade recently, engaging in a series of testing sessions with users to assess the usability of a product that we’re working on for a client.

We had made some extensive changes to a particular mobile workflow, and needed to create a testable artifact as quickly as possible. This scenario is well understood in the UX design world, and is pretty much par for the course when taking a Lean approach to creating a product. In this case there was a striking observation that emerged during testing that surprised us all.

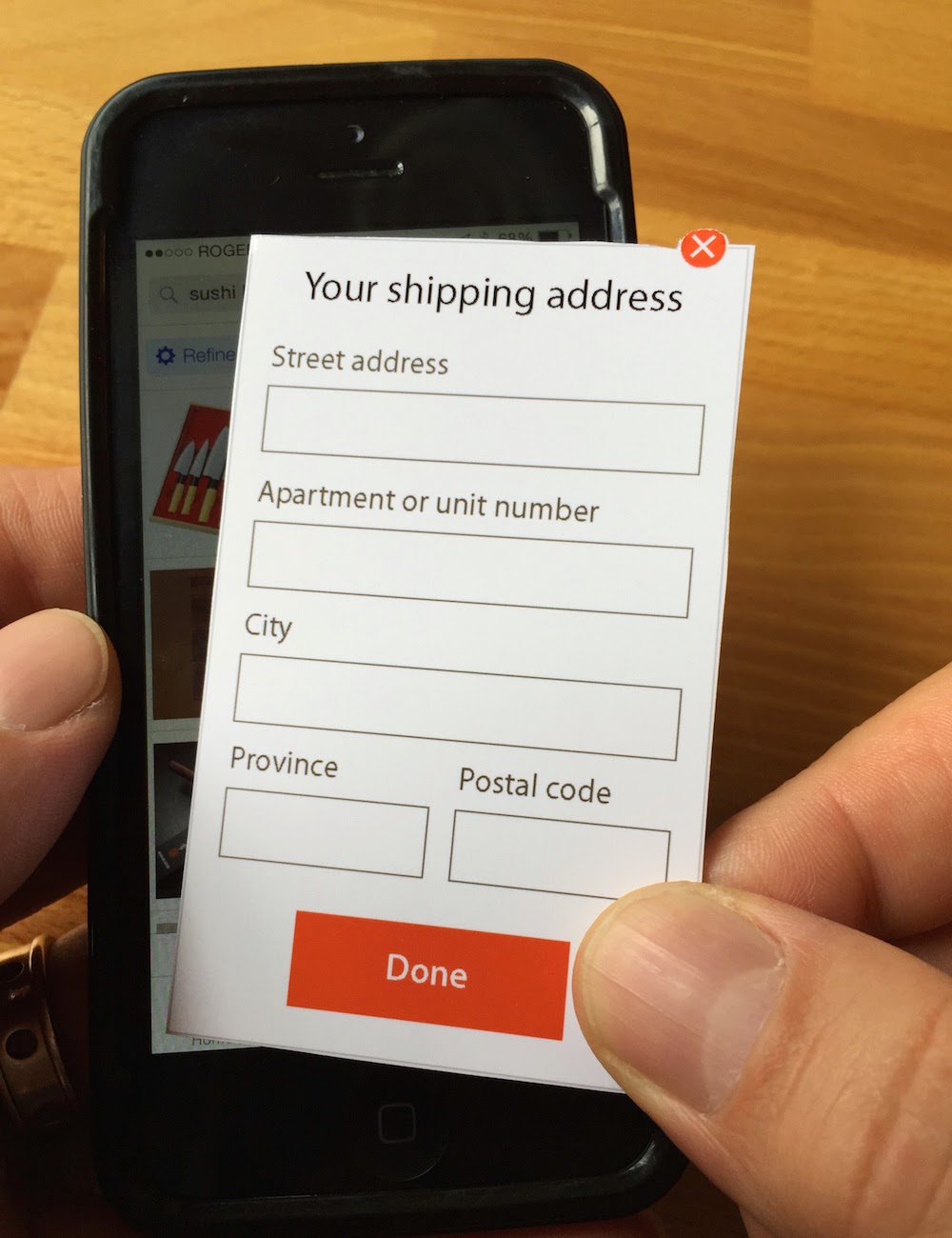

The test artifact that we created used a mix of approaches: an existing product was used to show functionality that was already well-understood; paper screens were created to show new functionality; and a human simulated the product back-end by sending appropriate feedback messages through the existing product in response to user input.

We had a test rig set up that enabled some of the team to observe from another room while a user interacted with the new design on a mobile device. It was easy to watch progress on a large screen during each testing session and, as always, there were useful insights that emerged.

Every time the paper screen was overlaid on the mobile device by our test facilitator we chuckled, as it looked funny to see the paper slide into place on the big screen. None of the users, though, had any trouble with the switch from pixels to paper and back again. And the messages that were sent by one of our team to the mobile device created a smooth and easily understood experience.

But the most striking thing we saw only became obvious, even to us, at the end of the day.

Despite the test artifact being a mix of real and fake functionality that included pieces of paper overlaid on a device screen, it felt “real”. Each user was even asked to “enter” information onto the paper “screen”, and to then watch the response on the mobile device screen; it still felt “real”.

And it was “real” to such an extent that every user we tested with told us, either unprompted or when asked, that the messages they saw in the mobile app were coming from a system with some kind of clever A.I. behind it. The workflow provided such an immersive experience that even paper screens did nothing to break the illusion that we were testing with a “real” mobile app.

When testing a hypothesis in a Lean context, you don’t need to build a fully functional artifact. All you need is an artifact that is good enough to learn from during testing. And that can mean designing and prototyping before starting to build.

This post also appears over on the Boltmade blog.